“When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life”. So said Samuel Johnson, the renowned 18th century wit. Johnson’s quote has been clung to over the years as the last word on the UK capital and to this day adorns posters and t-shirts, blogs and book titles. Like a lot of famous epigrams it’s at best half true.

The front of Tate Britain. Photo Credit: Tate Britain

You can certainly get tired of London. I used to live there and I did. Its sprawl, its pressured low grey skies, the stern faces on the Tube. These things can wear on you. When I was done with London I used to go to the Tate.

The Tate gallery everyone knows is the Tate Modern, whose 5 million visitors a year make it the world’s most-visited modern art gallery. I preferred the other Tate – Tate Britain. It’s smaller than Tate Modern and housed in a beautiful late-Victorian clean white neoclassical building overlooking the Thames at Pimlico in west London.

The site has been expanded multiple times down the years, though the grand porticoed room that greets you at entry and the gallery’s central dome are part of the original building. The most recent improvement was a 45 million pound renovation finished last October, the centerpiece of which is a beautiful new spiral staircase beneath its rotunda.

Tate Britain is the original Tate, but when Tate Modern opened its doors in 2000 inside an old power station on London’s Southbank, much of the collection moved down the river to the new site. The loss of the big name artists (you won’t find any Picasso’s at Tate Britain) mean the museum is often overlooked for its more famous sister gallery. From the point of view of the museum’s curators this might be a shame, but for the casual visitor it’s great.

It means you don’t get the same hordes of tourists cramming the gallery space that you’ll find at Tate Modern. For this reason I always found coming here calming, a release from the maelstrom of the city. The sense of release begins before you reach the museum. Despite its proximity to central London – it’s less than a mile from Big Ben – Pimlico has a low key vibe. After you get out the Tube and walk through the quiet residential streets of immaculate regency architecture you seem to leave the metropolis behind.

Less is more

The trouble with so many of the world’s top museums is over abundance. The sheer volume of stuff on display in these great repositories of culture can leave the visitor feeling more overwhelmed than enlightened.

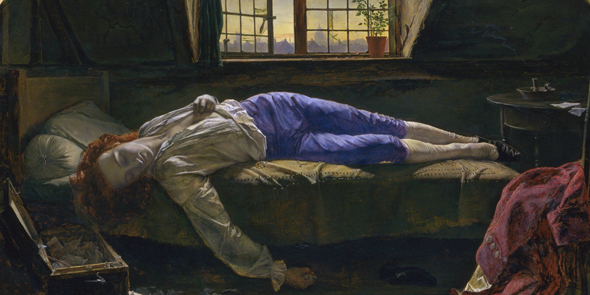

Henry Wallis’ painting of Thomas Chatterton is one of the museum’s most famous exhibits. Photo Credit: Tate Britain

Ironically, the loss of much of its collection has helped solve this problem at Tate Britain. As the name suggests Tate Britain only exhibits works by artists from the British Isles, the collection spanning the history of British art since 1500.

In this sense Tate Britain has come full circle. When the gallery opened in 1897 it featured eight rooms containing only British art. This return to its roots has helped focus the collection and walking around its elegant white interiors there’s a clear story being told. At first glance the story might not seem that interesting. Britain has never been too known for its painting. We contributed nothing to the Renaissance and no great art movements like Impressionism grew up on these shores.

Instead British art has been about lone geniuses, misfits and outsiders. So it’s their story you learn about at Tate Britain.

One of them was the poet and engraver William Blake. A contemporary of Blake’s was J.M.W Turner. One of the few pre-twentieth century British painters to gain recognition outside of his homeland, Turner was dubbed “the painter of light” for the iridescent quality of his oil landscapes and while he was a big influence on later painters like Monet his compositions, which sometimes drift into abstraction, were frequently derided by contemporaries.

‘That man who paints those dreadful pictures’

Both Blake and Turner are well-represented at Tate Britain – Turner’s landscapes and seascapes are mesmerizing to behold up close. The outsider tradition they both attest to continued into the 20th century and nobody embodies it better than Francis Bacon. Described by Margaret Thatcher as “that man who paints those dreadful pictures” Bacon was a bon viveur with a deeply sadomasochistic streak who worked as an interior decorator before he found his uniquely disquieting voice as an artist.

Tate Britain houses Bacon’s triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.

I’ve stood in front of its weird mutated forms many times trying to work out what’s so compelling about it.

Maybe what draws me to it is that other common theme running through British art: an overriding preoccupation with death. Whether it’s Sir John Everett Millais’ fragile Ophelia floating, flower in hand, through the reed beds or the pre-Raphaelite Henry Wallis’ depiction of the lifeless body of romantic poet Thomas Chatterton (both in the Tate’s permanent collection), British artists often seem at their most inspired when confronting oblivion.

The Golden Bough by J.M.W Turner. Photo credit: Tate Britain

This is certainly true of the biggest name of the so-called Young British Artist movement of the 1990s, Damien Hirst. From his headline-grabbing diamond-encrusted skull to his animals in formaldehyde, death is the subject of almost all of Hirst’s best-known work. His 2006 work Monument to the Living and the Dead on show here is an unusually subtle meditation on death containing butterflies on contrasting black and white backgrounds.

A glorious misfit

My favourite of the artistic misfits showcased at Tate Britain is William Blake. A one-man cottage industry his skills as a poet, painter and printmaker in 18th century London were largely ignored in his lifetime but the series of illuminated books that he bequeathed to the world are now considered some of the most important works in British art.

Deeply spiritual, he hated the encroachment of science into modern life. One of his best-known works on show here is his depiction of Isaac Newton. The famous scientist is shown at the bottom of the sea, a semi-naked figure crouched over a scroll as he draws with a compass.

Here’s another quote that’s hung on down the years that’s much better than Johnson’s. It’s from Blake.

“To see the world in a grain of sand, and to see heaven in a wild flower, hold infinity in the palm of your hands, and eternity in an hour.”

It encapsulates the point he’s getting at in his painting of Newton: that by obsessively measuring the world you don’t stop to contemplate its profound beauty.

On days when city life had beaten me an hour in Tate Britain was my little piece of eternity. It was something I never grew tired of.