In the Land of the Eternal Blue Sky, unpredictable adventure awaits. Genghis Khan’s former empire ranks among the lowest population densities in the world, with less than 3 million people, half of whom live in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. Sandwiched between historical occupiers and competitors China and Russia, the nation of nomads is carving its own cultural and political identity. Mongolia’s shift toward modernity has been hastened by global warming’s impact upon the treasured landscape.

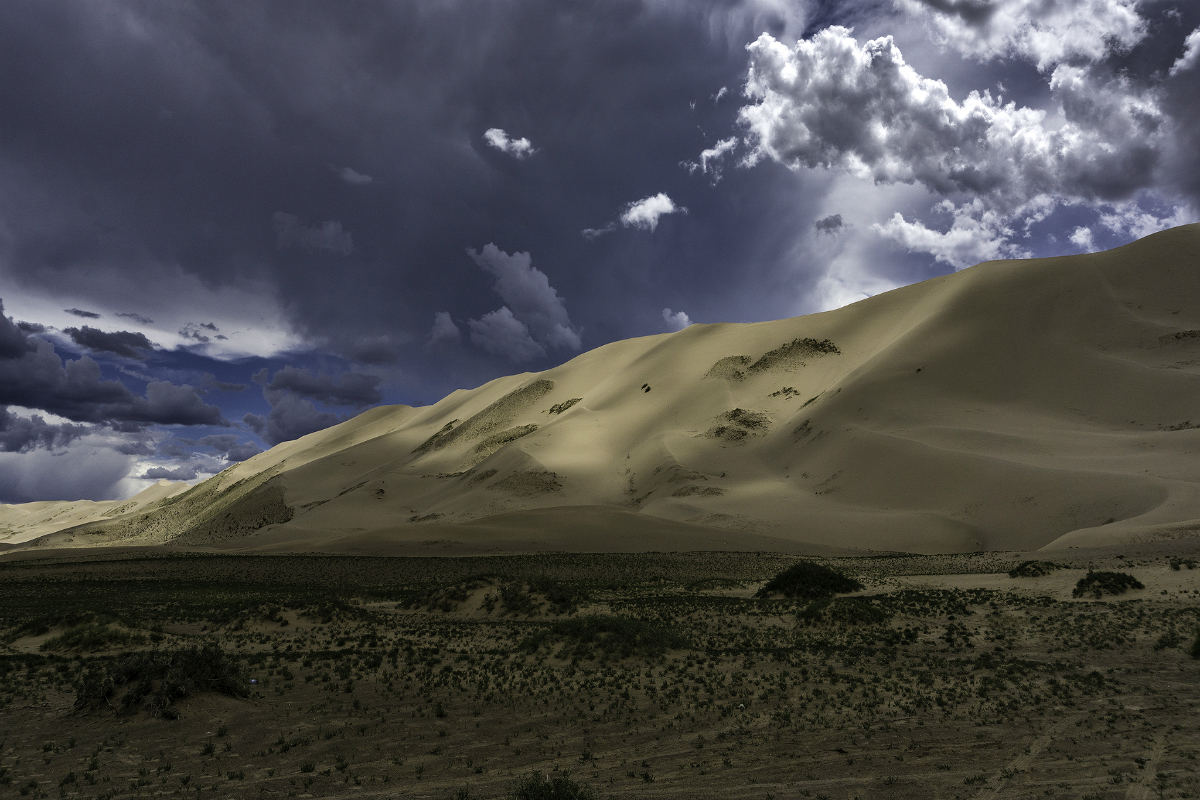

The iconic Khongor Dunes, located in the Gobi Gurvan Saïkhan National Park (Photo: Enguerran Zandonai)

The Gobi Desert’s Khongor Dunes

Sun-drenched sand slid over our flip flops, singeing our feet as they sank into the sea of granules. Up ahead, rising into a baby blue sky, the dunes grew steeper, flecked with dots of hikers in various stages of progress toward the ever-shifting peaks. Our Horseback Mongolia guide, Orkhon (a.k.a. Orgi), had said the dunes were 200 meters high, but constantly shifting. Each breeze, each step from above, sent a ripple of sand down the “singing dunes,” known for the low hum made by the moving sand.

“Should’ve worn sneakers,” my husband Tom and I repeated every few steps, though bare-feet seemed the best option for forging through the sand. Despite our efforts, our sandals sank, as if stepping into freshly fallen snow, making a jog on the beach seem leisurely. While eying the peaks from the van, I’d secretly worried that at almost seven months pregnant, I could not make it to the top. The blazing sand was a surprise addition to the challenge.

Yet Orgi had not seemed concerned about me attempting the climb, as she had been for each previous hike. A few days prior, when we’d asked if we could walk the five miles back to camp from the Orkhon Falls, she’d eyed my belly suspiciously, then relented only after I accepted her cell phone, in case I needed our driver, Banza, to rescue us. I never called. Ever since, she had offered a hand and a smile whenever we climbed down a rocky slope, but no longer questioned my desire to move as much as possible. She’d even stayed in the car, saying she would join us if we attempted another climb around sunset, the best time. Her faith in my ability to summit not once, but twice, was a refreshing change from the caring, yet irksome demands of elderly women back home, pointing at me to sit down on the Busan subway.

A gust of wind, though a refreshing relief from the midday heat, sent an assault of sand against my bare arms and face. I looked ahead at Tom, who was carrying our three-year-old daughter, Emi, in a pack on his back, and regretted siding with short sleeves and shorts to keep her as cool as possible, rather than opting for full coverage against the sun, and now, the raging sand.

“What should we do?” I asked, catching up to Tom, who stood paused at a dip in the dune before the great rise. “Ask them to drive us back to camp so we can change our shoes?”

We were torn and both so tired of being in the van, bumping across the barren steppe, on or off a track. We had not traveled on a paved road since we’d left Ulaanbaatar, eight days ago. If we drove the 30-minutes back to the ger (yurt) camp, would we actually come back to the dunes?

Another sand-filled gust. A whimper from Emi, followed by a fearful cry about a line of lazily approaching cows. Herding remains the primary source of income for nomadic families. One night, as we were nearing sleep, we’d heard a storm of stomping feet tromp through camp. Our unease turned to laughter when we heard the first moo, as it did the many times Banza honked his way through an aloof herd.

“They’re coming!” Emi yelped, suddenly afraid of the livestock she’d been excitedly reporting from her car seat during our long, bumpy drives. “Mommy, sheep!…Daddy, horses!…Camels!?!” A few hours prior, she’d rode a camel, then walked confidently into a herd of goats being separated by their owners after their morning foraging. Unfazed by their blurting and shuffling, Emi had befriended a beige kid, nuzzling its moist nose with her own.

Emi befriending a kid mid-sorting (Photo: Bre Power Eaton)

“THEY ARE COMING!” Emi hollered again, pointing frantically at the bovine crew, her voice trailing into a quiver as she hid her face against Tom’s shoulder. At the bottom of the small hill, a few furry, horned cows moseyed past, further complicating our moment of indecision.

Would we ever have a chance to climb the dunes again? The obvious answer hovered, unuttered. Now or never.

Despite Emi’s cries, we started down the dip, trudging toward the next rise, moving as quickly as possible to limit the time each foot sank into the burn.

“Emi, hide your face in Daddy’s back,” I urged as the wind grew stronger. I caught up to Tom and began snapping the pack’s small sun shade over her head. “Tuck your arms in, Honey,” I said, scrunching against Tom to avoid the now steady sting of sand against my bare back, arms and ankles. He tried to shield us with the circular plastic snow sled we were given to slide down the dunes, an effort that had failed—Tom and Emi being too heavy, the small hill not steep enough to gain speed. And, the cows.

On the drive over, Tom had asked Orgi if there were places to rent surfboards to ride down the dunes. Nope. Snowboards? Nope. Motorcycles or ATVs? Thank God, no. He has a knack for pulse-racing adventure that often leads to injury. Who knew how long it would take to get to the nearest village, much less what level of medical care awaited there. Surprisingly, the Gobi desert was neither entirely covered in beige, beachy sand (more like dirt and pebbles), nor heavily commercialized with the touristy vendors, which were likewise lacking throughout the country: the beauty of visiting Mongolia.

Suddenly, the wind turned ferocious. The steady borage of sand sent me huddling ever-smaller behind Tom until I heard Emi begin to cry and looked up to see her bare skin still exposed.

“Let’s go!” I yelled to Tom, my voice cracking into one desperate sob as I struggled to shield Emi. “Go, go, go!”

Hobbling through the hot sand en masse with our pathetic plastic shield, we made it back to the van. Defeated. We’d come back for sunset, we all agreed, if the wind died down. Meaning, in my mind, we were never coming back.

In the distance, grey sky loomed. Was it an approaching rainstorm or a dust storm or just grumpy sky taunting the parched desert? In just over a week, we’d learned the weather here is unpredictably fickle, one of many reasons why we were not supposed to ask Orgi how long each drive would take. Predicting a journey’s length is bad luck. Who knows what weather surprise awaited, much less what it would do to the roadless terrain?

What we would see each day and how long we had to explore each destination depended entirely on the weather. While frustrating, our weather-dependence paled in comparison to that of the nomadic peoples, whose lives remain inextricably linked to the land, shaped and nourished or denied by the whims of Nature. A link we all have, really; a link that becomes easier to ignore as lands bloom highways and high rises. Here, where a third of the population moves season-to-season to wherever their animals can find the most feed, this dependence is undeniable.

Nomadic Heritage

Nomadic gers in the Orkhon Valley (Photo: Enguerran Zandonai)

A few days into our trip, after another long, bumpy drive, we’d arrived at our host family’s home—a trio of circular gers. Dung and wood fires kept the one-room-residences toasty, releasing the stove’s smoke through an opening at the peak of the cylindrical roof. Inside, we each had a stiff twin bed and a pillow, often filled with grain. For our host families, these beds were multi-functional, serving as spaces to sleep, sit, eat and do chores.

When imagining what our homestays would be like, I’d hoped to be involved in the families’ daily lives—learn how milk a goat, cow, sheep or horse. Maybe even how to make yogurt or cheese. But the lack of rain that spring and many previous springs had led to a low supply of milk, Orgi had explained: the animals could not find enough vegetation to eat to produce enough milk for their young, let alone enough fat stores to survive Mongolia’s increasingly frigid winters. During a record-breaking winter in 2010 (dipping as low as -40 degrees), upwards of eight million animals died, leaving thousands of nomadic families with no source of income, forcing them to leave their traditional way of life behind and move to the capital to fight for limited jobs, with limited skills.

A Mongolian herder (Photo: Enguerran Zandonai)

Still, being out in the countryside, sans electricity and running water, disconnected from the world while observing an ancient way of life (suddenly, humorously, interrupted by a herder’s cell phone erupting a techno beat or another whizzing by on a motorcycle) offered us a nibble of the modern nomadic lifestyle. We were offered milk tea, made with earthy, pungent yak milk boiled with tea leaves, whenever we entered a family’s ger and watched Emi frolic with any children she could find, using laughter as a means of communicating when language failed.

One day, we left camp to visit a nearby waterfall, only to find it had dried up. Mournfully pointing to the rocks over which a torrent of water had once flowed, Orgi said, “Global warming,” her two-word refrain throughout the trip. “The land should be much greener now, covered in wild flowers. The animals…” she would repeat, then sigh.

The once glorious Orkhon Falls (Photo: Enguerran Zandonai)

After another full-day drive through arduous mountain terrain, we’d arrived at another family’s ger camp. As I squatted impatiently in their roofless wooden outhouse, aiming at a cantaloupe-sized hole in the ground I could barely see, a mix of light rain and mist pattered on my head. The wind shook the wooden planks underneath my feet. I imagined being swept up by the wind, trapped inside the rickety structure, flying over the valley a la Wizard of Oz. I held my budding basketball of a belly and wondered, “what am I doing here?” Though the trip had been a memorable experience—full of captivating landscapes and interesting conversation about the nomadic lifestyle—this wasn’t the first time I’d asked myself this question.

The previous day, while characteristically lost in thought, I’d forgotten to duck while exiting our ger and wacked my head against the low door frame, sparking instant, annoying tears. Yes, it hurt to run smack into a door frame. Yes, I felt stupid for doing it, yet again. But, I knew there was a deeper cause for these tears, stemming from a question that always followed the first: “Who am I to ever complain?”

When we’d first arrived at the second family’s home, the wife greeted us with her young son and teetering, rosy-cheeked toddler. Her husband was hours away at the village, trying to gather supplies to rebuild the gers that were destroyed during a recent storm. At one point, because of the destruction, we were not sure whether we would be able to stay with them or need to find a tourist camp instead.

That night, after a quick hike cut short by the wind, we sat around our host family’s ger, quietly enjoying the steaming hot vegetable soup she had made, along with flour dumplings. Near sunrise the following morning, I woke when the woman entered our ger to restart our fire.

“Bayarlalaa,” I said, thanking her for the added warmth with a sleepy smile, feeling a bit guilty she was already up and working, while I cozily spooned my dozing toddler.

Before we left, she came by our ger again to say goodbye. Following the custom of gift giving, we handed our host a small bag full of coloring supplies and stickers for the kids along with some hard-to-come-by toiletries and even harder-to-come-by cash (as bartering is still common in the countryside). She left but soon returned and held out two tiny, colorful coats.

“Choose one for Emi,” Orgi translated. “She sewed them by hand.”

Emi picked the purple one with the bright blue and gold trim. As she tried it on, my eyes again filled with tears. I hugged the woman, who’d just lost so much, yet gave us so much, and said, “Bayarlalaa,” knowing this word failed to capture all I really wanted to say.

A Tough Climb Ahead

As the sun began its descent over the Gobi, the wind settled. Air cooled. If we wanted to catch the sunset from the top of the dunes, we had to hurry. Tom strapped Emi to his back, and I followed a few steps behind, admiring the sky’s shifting hues. Streaks of orange, pink, and purple blended with the darkening blue expanse.

This time we began in our running shoes, but quickly took them off and huffed ahead with bare feet. At first, the cool sand was a relief, but soon, each sunken step only increased the burn in my calves. I took my time, pausing to admire the sky, the dunes, the fact that we were even here, a mental trick I’ve honed during marathon training—distract from the pain by refueling on gratitude. But every time I looked up, hoping to be closer to the top, it still seemed unfathomably far away.

Tom and Emi hike the dunes, racing sunset (Photo: Bre Power Eaton)

“I don’t know if I can do this,” I hollered to Tom, who replied encouragingly that we were a third done. I could do it. I didn’t have to, but I could.

And, I knew he was right. Though pregnant, I was not incapable, even if I had begun to feel treated as such. Women’s bodies, more than men’s, seem open for public discussion, and even more so when pregnant, as if contributing to mankind means that all of mankind is now responsible to tell her how she looks, when she should rest, and what she should eat or avoid. Confusingly, these regulations vary around the world. While pregnant with Emi in Japan, for example, I ate sushi regularly, per my Japanese friends’ nods of approval, but I avoided the “no-no” once I returned to the States. While I appreciate friends’ and strangers’ efforts to help—“Don’t bend over! Let me carry that!”—at times, I find myself annoyed, like a child wanting to prove she can do things for and by herself. And, there are only so many times even a person with a healthy body image can hear, “You are getting so big!”

Tackling this rugged landscape felt like a mini-rebellion. As I lagged behind Tom, though, I struggled to ignore the disparate voices bouncing around in my head, saying that I should and should not be attempting this feat. I paused to take a few deep, slow breaths and check myself: was my pride overshadowing my responsibility to care for the life growing inside me?

My legs were burning, and yes, I was tired, but my heart was not racing and my breath was steady. So, I started again, admiring the sky, the feel of the cool sand between my toes, and then my fingers, when I followed Tom’s decision to climb on all fours, which I soon realized was not a decision: the sand was too deep, the incline too steep, to walk upright.

A mid-climb breather (Photo: Bre Power Eaton)

Up, up, we climbed, sending ripples of sand sliding down behind us, changing the shape of the dunes, like the wind, like the climbers up ahead. Screaming young men and women flew by, racing down the slope in sleds, their faces reflecting expressions of both glee and horror.

Two-thirds of the way up. Only a third to go. We paused to rest and devise a strategy. Stop looking up. Count four steps, then pause for breath. Slowly, tortoise-like, with arms, legs, fingers, and toes aching, we willed our way up the dune. Fellow climbers cheered Tom on for carrying a kid. As if fulfilling her stereotypical role, every few minutes Emi complained, “Can I get out yet?” I couldn’t blame her. She wanted to be a part of the action, but the risk of her little legs tripping and sending her down the slope was also too steep.

Near the crest, Tom passed another tired climber who yelled profanities in exasperation after realizing, “You have a kid on your back?” Exasperation that doubled when Tom added, “And she’s pregnant!”

Laughing at the climber’s mini-melodrama was a relief, as was seeing Tom finally sit on the thin strip of flat sand at the triangle’s peak. My final few steps—hand-foot, pull forward, hand-foot, pull—required all the energy I had left. Plopping down on my bottom at the very top, my body tingled. My veins thrummed, pumping pure exhilaration. Though the sun had long set, the horizon was an enchanting mix of fading color and darkening clouds. The dunes hummed, sounding like echoing ohms, drifting in from distant Buddhist monasteries. Below and behind us, the parched steppe stretched endlessly. We were on top of the world.

And now, as the sky quickly darkened, we needed to get down. Fast.

Tom grabbed Emi’s feet and began to slide her on her bottom down the slope. She giggled and screamed, echoing the glee of those who’d passed us on our way up. Afraid to tumble forward, I followed suit, scoot-sliding down on my bottom, making waves in the cool sand, leaving a temporary mark behind on this ever-evolving landscape.

Special thanks to Horseback Mongolia for their flexibility, hospitality and expertise. Note: This story was based upon Bre Power Eaton’s personal travels. She did not receive comps for this story.