Few people, even those born and raised in the heart of Silicon Valley, have any inkling as to how their computers work. There are three tech museums that strive to reverse that trend. Who knew high tech could be so fun and fascinating.

Apple Computer Prototype, (Photo: Bill Strubbe)

Computer History Museum

The museum began in 1979 as the private collection of Gordon Bell, founder of Digital Equipment Corporation. Later the ever-burgeoning electronics cache logically migrated West to Santa Clara, CA; arguably the world’s techno epicenter.

Among several exhibits are “Innovators of the Valley,” including such luminaries as Douglas Engelbart, inventor of the first mouse carved from wood with a single button; Bill Hewlett and David Packard who began Hewlett-Packard in a garage in Palo Alto; and the two Steves – Wozniak and Jobs of Apple fame. The exhibit “Mastering the Game” chronicles the history of computer chess, culminating with a video of the defeat in 1997 of world champion Garry Kasporov in the face of the program wizardry of his computer opponent, Deep Blue.

But what I found most intriguing was the vast “Visible Storage” exhibit heralded by towering shelves packed with early computers. Near the top I spotted my first Apple 2c. On display are Asian abacuses and slide rulers, and an exhibit on Joseph Marie Jacquard, the Frenchman who developed the loom using a sequence of pasteboard cards with punched holes – the forerunner to binary punch cards. Further along was an orange, space-age-looking kitchen computer for recipes (but costing $10,000 in 1964, index cards were a better bet). This was followed by Xerox’s first laser printer ($100,000), and the first assemble-it-yourself Apple-1 from 1976 (for a diabolical $666.66).

In addition to the famed Norden bombsight of World War II, on display are vacuum tube panels from the Sage System developed by IBM for air defense. One of 27 massive computers installed around the country, they weighed 300 tons each. A circular screen, with a convenient built-in cigarette lighter and ashtray, was monitored 24/7 for enemy aircraft. In use from 1954 to 1983, the U.S. stopped producing vacuum tubes in the 70s, but in a cold-war twist still continued to import them from the USSR.

I returned to the lobby in time to see the demonstration of the Babbage Engine, the first automatic computing engine designed in 1854 Charles Babbage. Due to cost overruns it was never built, but in 2002, faithful to the original drawings, one was constructed weighing five tons, consisting of 8,000 parts. At one end a guide cranked a handle, engaging the gears, columns of numbers and switches, producing the numerical result at the far end, where it is also printed out. It was amazing; Babbage was a tech geek way ahead of his time.

Babbage Engine (Photo: Bill Strubbe)

Intel Museum

Who better to visit the Intel Museum with than my brother-in-law, a consummate computer geek. “You need to understand that the essence of a computer is essentially zillions of little on and off switches,” he explained, priming me to better “grok” the museum. “Whether denoted by ones and zeros, punch out computer cards, vacuum tubes or silicon chips, they’re all versions of on and off switches.”

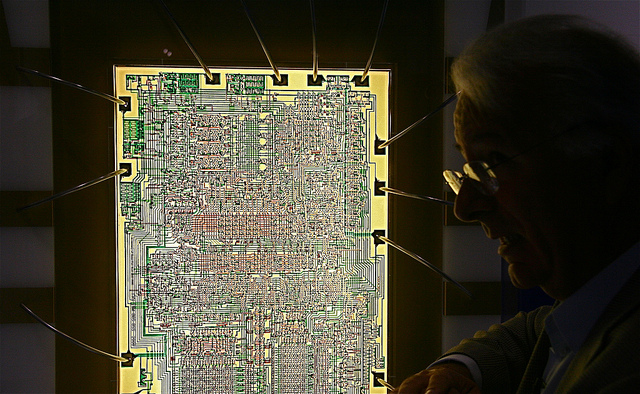

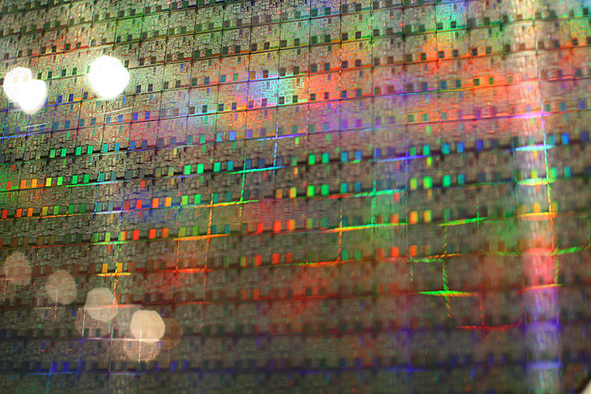

The Intel Museum, established in the early 1980s to archive the corporation’s history, opened to the public in 1992. As the museum tripled in size it also became a regional educational resource offering classes in electrical circuitry, technology careers, product marketing, and binary code. One of the 30 hands-on exhibits displays a full-size, silicon crystal that looks like a silver, cylindrical bombshell. Wafer-thin cross-sections of the crystal are sliced off creating round, LP-sized disks.

Further on I watched a graphic display of the sequence of multiple layers, etchings, and coatings each disk undergoes to create the grid of hundreds of microprocessors, eventually cut apart to become Pentium chips. John explained that employing the current process they will soon attain maximum reduction, and are now experimenting with building chips from the molecular level.

At one exhibit John followed the exacting instructions employees must follow for donning the proper attire (full-body coveralls) before entering the “Clean Room” where computer chips are manufactured. One speck of dust could screw up the works so hyper-vigilance is required.

Tech Museum of Innovation

With its vibrant, mango-colored exterior, the 132,000 square foot Tech is hard to miss in downtown San Jose, and millions have come to explore the world-class facility devoted to how science and technology is changing every aspect of how we learn, live and work. Even those who don’t consider themselves “techies” it offers something of interest for everyone. A certain sign of a successful museum is one where adults seem as happily engaged as their juvenile charges.

In the Exploration Gallery, I watched kids imagine they were astronauts navigating about in a chair resembling a NASA manned maneuvering unit (MMU) on jets of compressed air within an enclosed arena. Being an earthquake freak, I was drawn to the “Quake Watch” exhibit where a US Geological Survey program hourly updates recent earthquakes onto a digital world map. Here, I fiddled with seismographic equipment such as creep meters and strain gauges, but the most fun was standing on the “shake platform” to experience re-creations of historic earthquakes. After barely managing to remain standing for the simulated 7.2 Hengchun, Taiwan, quake, I was all jazzed up to see what the 8.3 Hokkaido jolt would be like.

Popping into the IMAX Theater with an eight-story screen and 13,000 watts of wrap-around digital surround sound we were immersed in the journey of the awe-inspiring “Humpback Whales” from the Tonga in the South Pacific to Alaska, learning how they communicate with one another, play and look after their calves. IMAX also offers: National Geographic’s “Robots,” a tour of labs around the world that are engineering robots to be less humanoid and more human; and “Jerusalem” exploring why this 5000-year-old contested city is important to so many cultures.

The Body Metrics exhibit blurs the boundaries between a museum show, research methodology, and a think tank presentation showcasing gadgets that don’t yet exist in the commercial markets. We were outfitted with a three-pieces of technology: a customized smartphone device; a Somaxis muscle and heart sensor; and a NeuroSky EEG headset, then set off to participate in activities including jumping up and down, basic yoga poses, conversing with others, and a table where small groups attempted to achieve calmness by synchronizing our heartbeats. After participating in the data gathering activities, we then laid our devices on the 12-foot touch table – the world’s largest touchscreen, to see the overview of health data. I was rated a “team builder,” while my friend was a “floating doer,” whatever precisely that meant.

All this tech stuff seems like fun and games, but in The Tech Awards Gallery, I was inspired by several talented innovators who have employed their technical and science skills to benefit the world’s less fortunate. Bunker Roy teaches India’s poor how to build rainwater harvesting systems and solar power panels. Founded in 2005 by Joshua Silver, Adaptive Eyecare allows low-cost lenses to be tuned to the individual’s prescription by pumping fluid to change the curvature of the lens; and The Kickstart Pump is a low-cost irrigation pump allowing farmers to pull water from the ground, rather than relying on rainfall. In the end, the ultimate purpose of technology is to improve the quality of human lives, and at the Tech one catches a glimpse of that brighter future.

Body Metrics Exhibit at Tech Museum (Stock Photo from Tech)

Further Information

Computer History Museum – 1401 N Shoreline Blvd., Mountain View www.computerhistory.org Admission is free.

Intel Museum – The Robert Noyce Building, 2200 Mission College Blvd, Santa Clara www.intel.com/museum Admission and parking are free.

The Tech Museum of Innovation – 201 South Market St, San Jose www.thetech.org. Admission is $21 for adults; $16 for students and children.