Get ready to stand in awe at some of the world’s most creative, controversial, unique, and unforgettable structures. For Modernist architecture, there is nowhere on earth like Kyiv.

Crematorium in the Park of Memory, Kyiv (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, is a city of some three million people. Founded in 482 CE, its oldest landmarks date all the way back to the era of the Kievan Rus’, the first East Slavic state, and two of the city’s religious sites are recognised with UNESCO World Heritage status: the Pechersk Lavra monastery complex and Saint Sophia Cathedral. In the mid-twentieth century, however, the city would be forced to undergo something of a rebrand.

Ukraine became part of the USSR in 1922. During World War II, the country suffered enormously under successive advances and clashes between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Red Army. The former made no secret of their intention to wipe Kyiv off the map; and in 1941, the Soviets themselves destroyed parts of the city centre, with remote mines they planted ahead of the Germans’ arrival. After the war, Kyiv would see a great deal of rebuilding, and in many cases these Soviet city planners embraced popular architectural styles from the West, such as Modernism and Brutalism, as they reinvented Kyiv for the 20th century.

Nowadays, Kyiv’s Modernist heritage can be a complicated topic. The style was so popular with Soviet planners and architects that for many people it has become emblematic of that regime. Whereas the same building, in a different country, might be evaluated purely in terms of its aesthetics and function, for many Ukrainians today the Modernist style is tainted by its perceived historical associations. Nevertheless, the city of Kyiv boasts some of the most creative, memorable, and technically impressive works of Modernist architecture in the world, as illustrated by the following examples.

Hotel “Salyut” in Kyiv, Ukraine (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Hotel “Salyut”

Hotel Salyut is one of the more striking examples of Modernist architecture in Kyiv. Opened in 1984, after eight years of construction and planning, it was very much a product of the space age, taking its name from the USSR’s “Salyut” space station programme (in a similar thematic vein to Hotel Gagarin in Odessa, Hotel Cosmos in Moscow, or Hotel Planeta in Minsk). Led by Soviet Jewish architect Avraam Miletsky (who will feature again in this list), the original designs and models for the building had its height several times higher – a veritable skyscraper at 18 floors. The base footprint was designed and built to support a much taller building, though this original vision was never realised, as the project was hindered by ongoing bureaucratic issues. Reportedly, the architectural team of Miletsky, Slogotskaya and Shevchenko refused advances from Party leadership to add the Party curator to the list of authors, and as a result, they had their funding slashed. Nevertheless, the final construction represented no less of an engineering feat. Rather than stairs, a spiral ramp corkscrews from the aluminium-panelled lobby, up the inner nucleus of the hotel; while walls of reinforced concrete fan out from here to define 89 hotel rooms arranged in 5 stacked rings.

Ivana Mazepy St., 11b, 01010, Kyiv

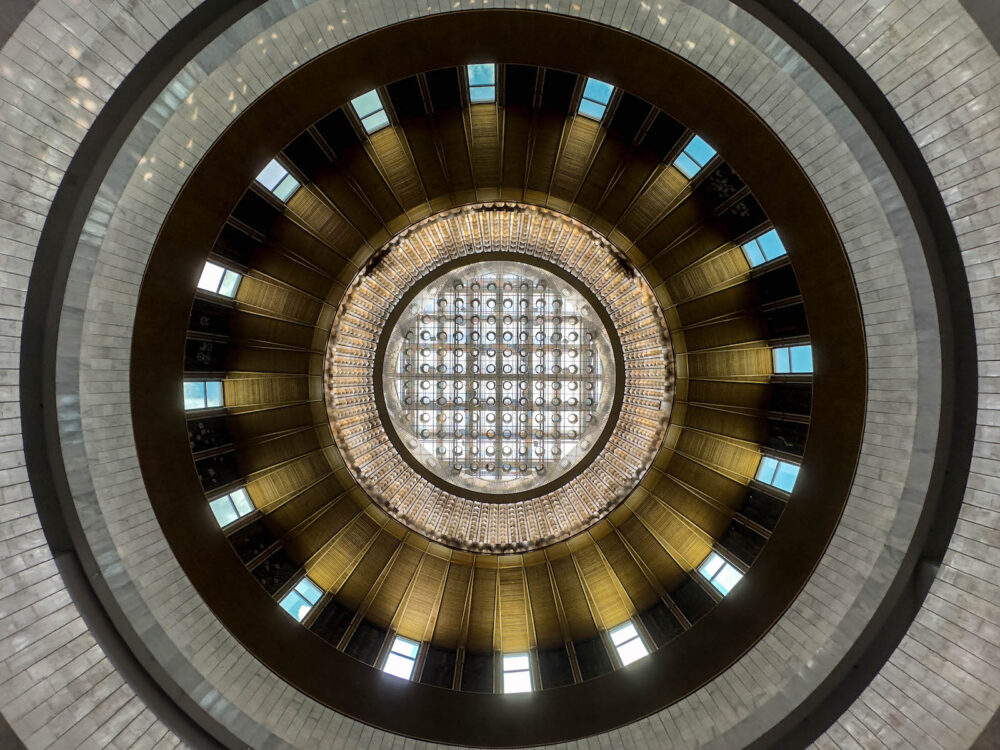

“Ukrainian House” International Convention Centre (Photo: Darmon Richter)

“Ukrainian House” International Convention Centre

This building at the top end of Khreshchatyk – a monumental white palace, a flattened cupola stacked on top of its square main body – was originally opened in 1982 as the All-Union Lenin Museum. It was built by the Kievproekt group (originally formed to rebuild Kyiv following the devastation of WWII) and would be a four-year project, headed by architect Vadym Hopkalo along with architects Volodymyr Kolomiyets, Vadym Hrechyna and Leonid Filenko. The original purpose of the building was to host a museum dedicated to Lenin, and exhibiting a range of items and materials that documented Lenin’s life. After 1993, however, the All-Union Lenin Museum underwent it’s own rebrand: to become “Ukrainian House.” In 2016, following the introduction of Ukraine’s decommunisation laws, further adaptations were made to remove some of the original Soviet bas-reliefs. Today the Ukrainian House remains the nation’s largest exhibition and convention centre, with space for 3,500 attendees, including an open main hall in addition to various additional rooms and galleries, conference spaces and even an on-site restaurant, all spread across five floors.

Khreschatyk St. 2, 01001, Kyiv

The Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine

Ukraine’s main academic library and scientific archive was founded in 1918, as the National Library of the Ukrainian State; before later adopting the name of its first director, the Soviet scientist and Stalin Prize recipient, Vladimir Vernadsky (who was born in Saint Petersburg and had Ukrainian heritage – his family allegedly being able to trace their roots to Zaporozhian Cossacks). Ukraine’s National Library is headquartered today in the Demiivka neighbourhood of Kyiv, inside an extraordinary, windowless, Brutalist tower. Rising to a height of almost 80 metres, the building was under construction from 1976 until 1989, under architects V. Gopkalo and V. Grechina. The 27 floors inside are said to host roughly 15 million items now, including many rare texts and archives. The interior of the building (which may be photographed only by prior arrangement) is quite incredible – with classical-styled marble staircases and historical busts, leading into bold Modernist spaces characterised by warm, bare concrete, round skylights, and more vegetation than one might expect to find in a library. The building is also filled with some notable works of art, including a large encaustic wax painting titled Pains of the Earth (Vladimir Pasivenko and Vladimir Pryadka, 1989), which adorns the main lobby with its classical retelling of the Chernobyl disaster: Icarus, wings alight, falls out of the sky while an atomic mushroom cloud rises on the horizon.

Holosiivskyi prospekt, 3, 03039, Kyiv

Institute of Scientific, Technical and Economic Information (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Institute of Scientific, Technical and Economic Information

One metro stop away from the National Library, at Lybidska, stands the building of the Institute of Scientific, Technical and Economic Information. It was created by architects Florian Yuryev and Lev Novikov, with an engineering team of A. Pechenov, L. Kovalev, L. Kovtun and N. Coffman. Built between 1964 and 1971, the complex consists of a 16-floor high-rise, attached to a larger base from which extends a saucer-shaped body containing a conference space. Somewhat resembling a UFO in design, many locals would affectionately come to refer to the building as the “Tarilka,” or “Saucer.” More recently, this unique building has faced questions about its future, with at least one proposal to demolish it and develop the site into a modern shopping centre. However, other parties have countered that the building might be adapted instead for new use as a museum. Some positive news came in October 2020, when the Institute of Information was added to Ukraine’s Cultural Heritage Protection registry.

Antonovycha St, 180, 03150, Kyiv

Zhytniy Market (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Volodymyrskyi and Zhytniy markets

Marketplaces were an important social fixture in Soviet cities, and during the era when Modernist architecture was at its peak popularity, many markets would be redeveloped as unique architectural spaces. Kyiv has a number of such examples. Volodymyrskyi Market, for example, on Antonovycha Street, features an incredible Modernist hall with full-height windows reaching up to a zig-zagging honeycomb ceiling (by architects G. Ratushynskyy and K. Feldman, 1968). Perhaps even more striking though is Zhytniy Market in the downtown area of Podil. Zhytniy is one of Kyiv’s oldest marketplaces, having operated here since the 15th century and the time of the Kievan Rus’. The site was redeveloped in 1982 however (by architects Valentyn Shtolko and Olga Monina), as a vast and metal-panelled Modernist hall. Natural light floods the space inside, beneath the grand sweep of an organically curving ceiling. Around the exterior meanwhile, metal reliefs by the artist Domnych Anatoliy represent traditional trade routes, detailing waves, ships, and the names of various Ukrainian and foreign Black Sea cities.

Verkhnii Val St, 16, 04071, Kyiv

Metal reliefs by Domnych Anatoliy represent traditional trade routes (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Obolonska Square Residential Buildings (“The Corn Cobs”)

Two unusual residential towers rise above the district of Obolon, in the north of Kyiv. The shape of them inspired the local nickname “Kukurudzi,” meaning the “Corn Cobs”. Situated on Obolonska Square (formerly Druzhby Narodiv Square), the two buildings rise to heights of 17 and 22 floors. The smaller building was completed first, in 1981, by the architectural team of M. P. Budilovsky, I. Ivanov, V. Morozov and V. Kolomiyets. The taller building was completed later, in 1990, by architect V. Ladnyi. The Obolonska Square towers featured a range of one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments, accessed via staffed lobbies, and during the late Soviet period these were considered to be very desirable residences. Time has since dulled their concrete a little though, while the privatisation of the apartments inside has turned their facades into a rather chaotic patchwork of mismatched windows, balcony conversions, satellite dishes and air conditioner units.

2 and 2a Obolonska Square, 04210, Kyiv

Autobus Park №7 (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Autobus Park №7

In the early 1970s, the commission was given to build a new transport depot on Kyiv’s Boryspilska Street. The brief specified that the new building should be able to house a fleet of as many as 500 city buses. However, the available floor plan was tightly limited. An innovative solution was found by the engineers V. A. Kozlov and S. I. Smorgon: rather than create a square building whose roof was supported on pillars, instead, they proposed a circus-like structure, featuring just one central support pillar (reinforced concrete at a diameter of 8 metres) around which a roof composed of concrete panels could be suspended on cables. Known as Autobus Park №7, the new depot was opened in 1973. The interior space made good use of natural light, from portholes in the ceiling and upright glass sections in the outer walls. For a time, it was considered the largest vehicle depot in the USSR, housing city buses covering most of Kyiv, as well as providing vehicle wash and maintenance facilities, and canteens for its on-site staff of 1,500. Today however, this remarkable building is in a serious state of decline. After being gradually phased out of use, the depot finally closed its doors in 2015, and now serves as a scrapyard for hundreds of decommissioned vehicles. Although many Kyiv residents have called for its conservation, the structural decay grows ever worse, so any such intervention becomes more difficult, more expensive, and thus, more unlikely, with each passing year.

Boryspilska St, 26к, 02000, Kyiv

“The Halls of Farewell” (Photo: Darmon Richter)

Crematorium in the Park of Memory

Soviet Modernist architecture is often caricaturised as masculine, blocky and cold; but the crematorium complex in Kyiv’s “Park of Memory” on Bajkova Hill – another creation of the Jewish architect Avraam Miletsky – presents a compelling counter-argument. Created between 1968 and 1981, the unusually-shaped buildings that form the centre-point of this complex – formally titled the “Halls of Farewell” – have been described as Neo-modernist, with organic, curving shapes that were allegedly designed this way to discourage any material associations with the actual process of cremation that took place inside. Indeed, during these first post-war decades, as Kyiv’s citizens were still coming to terms with the horrors of Nazi occupation and the massacres at Babyn Yar, the industrial incineration of corpses was still a difficult subject. Miletsky’s solution was to create an avant-garde ritual space for remembrance and reflection, and this was further developed through the inclusion of a monumental Wall of Remembrance created by artists Ada Rybachuk and Vladimir Melnichenko. However, there was later a conflict of ideas, stemming from different interpretations of the role of art in such a sombre site – which ultimately led to the Party leadership concreting over the Wall of Remembrance in 1982. It is only in the last few years that conservation work has been undertaken to begin uncovering and restoring Rybachuk and Melnichenko’s elaborate decorative reliefs.

Baikova St, 16, 03039, Kyiv

House of Furniture

The House of Furniture is located near Pechersʹkiy Bridge, on the Right Bank of the Dnipro River. The building’s roof traces an unusual concave curve between four angular corner posts, which gives it a uniquely organic profile. This design was the work of Ukrainian academic and architect Natalia Chmutina, who, in 1952, was the first Soviet woman to receive the prestigious Candidate of Architecture degree. Like many of the other top architects in the Soviet Union, Chmutina began her career by designing hotels – in Kyiv she worked on the Intourist Hotel (1952-1956), Hotel Dnipro (1959-1964), and Hotel Lybid (1965-1970). Later, in 1985, she would lead the restoration work on the Verkhovna Rada building, which is home to the Ukrainian parliament. Her House of Furniture (1971) was a somewhat more idiosyncratic proposal though, which Chmutina worked on with fellow architects A. Stukalov and Y. Chekanyuk. The design allegedly borrowed inspirations from the sloping roofs of vernacular folk architecture, while the interior consisted of large and bright spaces for trade and exhibitions.

Mykoly Mikhnovskoho Blvd, 23, 01133, Kyiv

National Palace of Arts “Ukraina”

The National Palace of Arts was opened in April 1970. It was designed by Yevhenia Marychenko, who worked with fellow architects P. Zhylytskyi and I. Weiner, over five years, to create a venue that could host concerts as well as official Party congresses. All of its architects were awarded the Shevchenko National Prize for this building – which incorporated a main hall with capacity for over 3,700 people, and in total more than 300 rooms facilitating a diverse range of cultural functions, with interior spaces and lobbies designed by the renowned Ukrainian architect Irma Karakis. The architectural researcher Dmytro Soloviov, of the popular Ukrainian Modernism account on Instagram, points to the cosmopolitan qualities of its construction: “The walls of the palace are made of Kazakhstani limestone, the stylobate, stairs and retaining walls are lined with grey Ukrainian granite, the interior is lined with white Ural marble, and Carpathian tuff.” As a venue, the Palace of Arts has hosted international acts including Luciano Pavarotti, Enrique Iglesias and Lana Del Rey, and in 2013 it was chosen as the venue for the Junior Eurovision Song Contest. Whereas many other examples of Soviet Modernist architecture in Kyiv today face mixed assessments (and those more explicitly political in their decorative art or symbols have fallen foul of decommunisation laws), the National Palace of Arts is for the most part well appreciated. While some original design features were lost to a 1996 renovation and remodelling, in 1998 it was recognised with the status of National Palace, and today, Soloviov notes, it is “one of the few officially listed Modernist buildings in Ukraine.”

Velyka Vasylkivska St. 103, 03150, Kyiv

Inside Autobus Park №7, Ukraine (Photo: Darmon Richter)